Detroit is the epicenter of failed capitalism in America. The city has suffered decades of neglect as capital has fled, leaving a majority African American population to suffer the consequences, including high unemployment, poverty, and the gutting of public services. Yet, things are about to get worse. Kevyn Orr, the city’s unelected emergency manager (as well as a wealthy Wall Street lawyer connected to the Democratic party) recently announced a plan to virtually eliminate pensions and benefits for current and retired city workers. Public services – including utilities such as water delivery and trash collection – will be privatized and public resources will be sold off at fire sale prices. Detroit is just the beginning. Wall Street, in collaboration with the state and federal government, is using the financial crisis to mount a neoliberal attack on communities across the U.S. From Baltimore, MD to Stockton, CA, cities in financial distress are closely watching what happens in the former industrial capital because it’s an example of what is to come.

The plan to restructure Detroit’s debt is neoliberal logic in action. Over the last forty years, as public funding dried up along with the city’s tax base, Detroit was forced to borrow to make up the difference. This borrowing resulted in windfall profits for banks and the global investor class. Now that a debt crisis has landed, Orr is proposing drastic measures. Yet, he plans to treat all debt as the same. A retired librarian relying on a city pension will be forced to swallow the same cuts as a Wall Street financier managing a multi-million dollar portfolio of municipal bonds. (In fact, some reports show that retirees will suffer even greater losses than bondholders.) That is what “shared sacrifice” looks like in our post-crash age. What can we do about it? Is there any alternative but to hope that a bankruptcy court can tell the difference between a teacher and an investment banker?

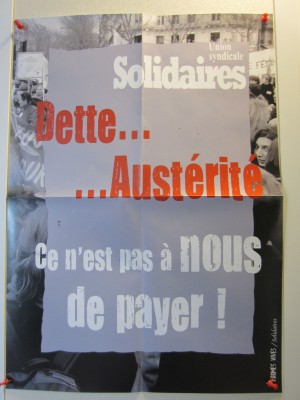

An alternative strategy of debt refusal is beginning to unfold in Europe and in the global south. Argentina stopped payment on a portion of its state debt in 2001, followed by Ecuador in 2008. Organizers in Europe were inspired to conduct audits of public debt with the goal of taking the power to determine the legitimacy of such debts out of the hands of politicians, bankers, and the courts. Since the European movement began in France, a broad coalition has emerged in multiple countries. Working under the banner of the International Citizen Debt Audit Network, regular people, most of whom are not finance experts, are studying the debts owed by cities and public agencies in order to determine which ones deserve to be repaid. Their slogan is “Don’t Owe, Won’t Pay”, and the goal is to reject the same kind of neoliberal logic being unleashed on Detroit.

As part of a global movement of debt resistance, we believe we can learn a lot from struggles unfolding around the world. A member of Strike Debt recently caught up with Patrick Saurin, one of the organizers of CAC, France’s debt audit network. Patrick is the author of a book on toxic loans and he will be speaking about public debt at the Committee for the Abolition of Third World Debt Summer University event later this month. The following is an edited and condensed transcript of the conversation.

Patrick: We used to have Sarkozy and now we have Hollande, but they’re basically the same. The political situation has not changed in France, unfortunately. The socialist party is a bit better than the right, but they operate by the same logic. Nothing will change. Before Hollande’s election, there was a government commission created to study toxic loans. They wrote a report and analyzed the problem. The report suggested that an audit run by the government and by institutions was necessary. But we think that citizens, regular people, must be the ones to conduct the audit.

SD: Why is it important that people in local communities take part?

Patrick: It is important that people are invested in the process. Our society is very individualistic and it’s difficult to get people to think in terms of a collective. We want to encourage that kind of thinking. One of the things we do is distribute a brochure that asks people to test their knowledge about national debt and gives them the real facts. Two other brochures on our website explain how to audit the debt of a city and a hospital. This is one way to challenge the idea that we’re in debt because the government spends too much. One of our goals is to help people understand that overspending is not the reason we have this debt. Some of these debts are actually illegitimate and shouldn’t be paid back. This is what happened in some towns in France that refused to repay loans to Dexia, a bank that had been bailed out with public money.

SD: In the US, we struggle against a mythology that all debts deserve to be paid back. Is something you struggle against as well?

Patrick: In the U.S. you have cities and counties in debt, such as Orange County in CA, Jefferson County in AL, and Baltimore. It’s important to get large groups of people who are affected by debt to work together. In France we have unions, associations, political parties, and individuals. We work together but with clear principles that some debt is illegitimate. On our website, we have a short text that defines our principles, and it’s important to make these clear to people doing the work.

SD: What is the ultimate goal of the audits?

Patrick: The goal is to look at all the public debts and decide which ones are legitimate, legal, and have a purpose that serves the public. That debt deserves to be repaid. But debts that primarily enrich banks are illegitimate and should not be repaid. The goal of the audits is to make this distinction. The concept of illegitimate debt is growing. There are examples of countries that are not paying back their debt. With help from Eric Toussaint of CADTM, Ecuador analyzed its debt and the President, Rafael Correa, refused to pay back a part of his country’s debt. Germany did not pay back some of the debt it owed after WWII. So there is precedent for this. Another goal is to ask why is the state acquiring so much debt. Corporations and rich people are not paying taxes, or they pay very little. They have ways to lower their taxes through tax havens. The difference has to be made up somewhere. The state has to borrow. The goal of the audits is to ask why the public debt is going up. It’s not because we spend too much or we’re too often sick or something like that. It’s because the fiscal situation benefits banks and corporations. These debts are against the law. We actually want cities and public agencies to refuse to pay back these debts.

SD: What do you say to people who say that audits are not spontaneous or radical enough to jump-start the social movement that we need?

Patrick: I understand that people are impatient and I share their impatience. But my experience has convinced me that a movement worthy of its name will take a long time to develop. It will develop out of hard work, conviction, and changing people’s minds over time. Spontaneity and improvisation are necessary, but there is no good substitute for the kind of long-term work required to really be effective.

SD: What advice do you have for people in the US who want to conduct militant research on municipal debt?

Patrick: There is national debt and there is debt owed by cities, counties, and public agencies. Then there is student debt and housing debt, particularly sub-prime debt. Each is a particular case. But behind all these debts is a common element: fraud. We’ve been swindled. The mechanism may be legal, but it is immoral and illegitimate all the same and we need to fight against it. It’s not right that Baltimore, for example, fires city workers in order to repay the interest on toxic loans. It’s not right for students to go into huge amounts of debt for education and then not find jobs afterwards. It’s not right for people who bought homes on a subprime market to keep paying to enrich banks. For each of these categories, there needs to be a specific analysis and a specific tactic for how to fight back. That’s the work: for people affected by different categories of debt to fight back as collectives. For example, it’s important for students to join a “stop pay” movement based on the idea that education is a right, not a commodity. Education has no price. It’s important to reverse the fear, to change the way people think about debt and to convince them that things can be done differently. Health is a right. Housing is a right. We need to make this case. It’s difficult to have a global approach to the problem. There are so many different kinds of debt. But all of them are mechanisms to take away our future. The debt system steals our future from us. It imprisons us until the end of our days. That’s what all the types of debt have in common. And this is why we need to keep fighting.

Where do we go from here? In the U.S., some cities and groups are fighting back against toxic loans and illegitimate debt. Baltimore filed suit against a dozen big banks for manipulating LIBOR, the benchmark for interest rates on many financial products. The Chicago Teachers’ Pension and Retirement Fund is currently investigating the losses it sustained as a result of the scandal so it can attempt to recover some if its money. Activists in Oakland, CA are pressuring the city council to make good on its pledge to terminate toxic loans peddled to the city by Goldman Sachs in the 1990s. The question of how to organize audits of the public debt in the US on a national scale is a question worth exploring. As the movement grows, our comrades from abroad suggest that our power lies in uniting this work under the same banner. After all, local campaigns can have global implications. While regional strategies for resisting illegitimate public debt may differ, there is much work to be done based on the principle that unites us: “Don’t Owe, Won’t Pay!”