In an earlier post on this website, we told the story of Richmond, California, a small city with big plans to end its foreclosure crisis via a novel use of eminent domain. If successful, this plan could set a nationwide precedent, and Strike Debt Bay Area (@StrikedebtBA), among other groups, is fighting to push it through, against pressure from big banks and big government alike. But there’s a new twist on the concept of using eminent domain that could have far wider implications, not only for the foreclosure crisis, but also for the power of big banks. In this post we explore that twist—referred to here as “clouded chain of title”—and its potential implications.

By this point, many of us have at least heard of mortgage-backed securities and other financial products that gambled on future mortgage payments and lost, precipitating the 2008 financial crisis and throwing hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people out of their homes via foreclosure. Most of the gamblers (big banks, other financial institutions) have yet to pay for their bad bets, while homeowners and former homeowners—perhaps better understood as “debt-owners”—continue to struggle in the wake of Wall Street’s failures. A situation known as “broken” or “clouded” chain of title—a lesser-known aspect of the mortgage-backed securities story—may hold the potential to turn this around.

Put simply, in order for mortgages to become part of a financial instrument—to become “securitized”—they need to be pooled with other mortgages and then transferred from the originator (Bank of America, Countrywide, or whoever issued the original mortgage), to an aggregator, eventually ending up in a securitized trust for investors. For our purposes, the finer details are unimportant. What is important is that each of these steps requires a true and legal sale from one entity to the next.

The last step in this sequence—when the mortgage joins a securitized trust—is documented by a Pooling and Servicing Agreement (PSA). Each PSA has a cutoff date, and if the mortgages are not transferred into the PSA by the cutoff date, then that sale is not true and legal. (According to one of the lawyers we consulted for this article, the more accurate language is “a post-cutoff-date transfer is a void assignment,” taken from the court case Glaski v. Bank of America.) Missing the cutoff date for transfer into the PSA clouds the chain of title on the mortgage, meaning that the official record of ownership of a given mortgage is now muddled, throwing into question who owns that mortgage. The bank that receives your monthly payments doesn’t own the mortgage, since the bank is merely a “servicer” for the investors. The aggregator may or may not still own it, given that the aggregator received money from the trust it was ultimately placed in, and from that point on assumed that the mortgage was legally no longer in its possession. But the investors don’t really own it either, because it wasn’t transferred into the PSA before the cutoff date.

While this clouded chain of title situation may seem obscure and technical, it turns out that when the mortgage-backed securities market started heating up around 2005, and even before, an unknown but very high percentage of mortgages that were turned into mortgage-backed securities were transferred into their PSAs after the cutoff date. One industry insider told us that all non-Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac mortgages were transferred improperly. In other words, the ownership of potentially millions of mortgages is in question.

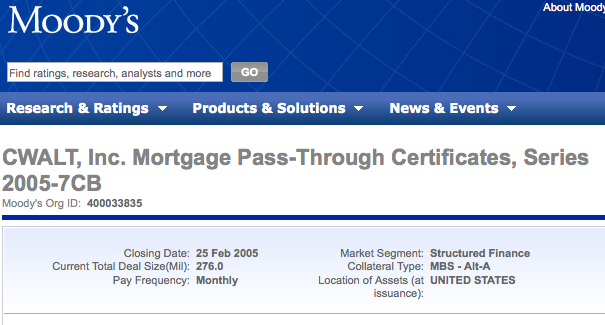

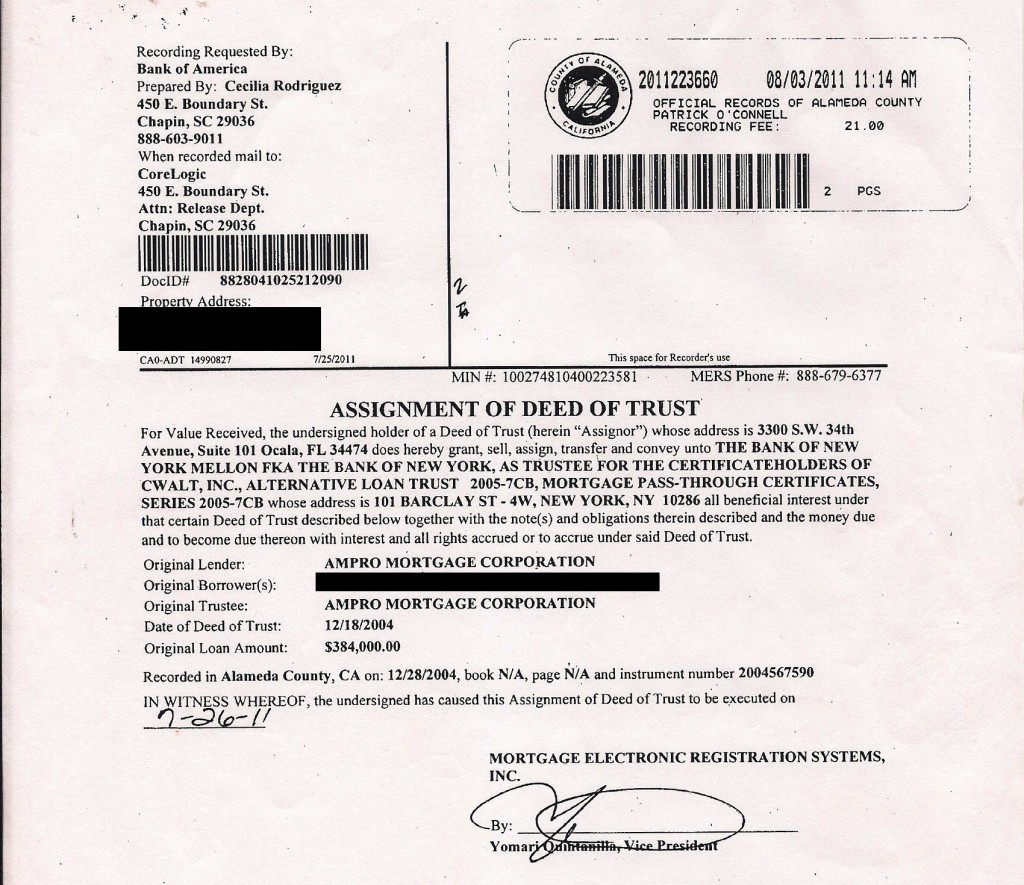

The closing date of the trust in the top image is February 25, 2005. The date of assignment in the bottom image is July 26, 2011. This mortgage was transferred into the trust more than six years after the closing date. Note that the two named entities are virtually identical, with just the component identifiers ordered differently: CWALT-INC, Series 2005-7CB, Mortgage Pass Through Certificates.

What does this have to do with systemic solutions to the ongoing foreclosure crisis and eminent domain? Put simply, if we can combine the eminent domain strategy that Richmond is currently contemplating with legal proceedings that force banks/trusts to prove that they own mortgages in their portfolios (which they can’t, because they don’t, as described above), we have the potential to wrest untold thousands of mortgages out of the hands of Wall Street. What we then do with them (and who might own them if not the banks or the trust) is another question. But first things first: what does this plan look like?

Here is the idea laid out in five steps, using Richmond as a hypothetical example:

Step 1: Find a willing Richmond citizen whose mortgage is in dispute. This will be easy given that, by insider estimations, after 2005 all non-Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac mortgages were transferred improperly.

Step 2: The city of Richmond steps in on behalf of this citizen, in an attempt to force banks (acting on behalf of the trust) to prove ownership of the mortgage. The city has at least two choices here: One, as a preliminary step before going ahead with the eminent domain seizure of this citizen’s mortgage, Richmond can ask a judge to determine ownership of the mortgage using something called “declaratory judgment law” (for legal folks out there, this is Cal. Civ. Proc. Section 1060). Put simply, declaratory judgment law asks the court to resolve a legal uncertainty. In this case, the uncertainty is, who owns this mortgage? In the declaratory judgment suit, the city would note that it is planning to condemn the loan via eminent domain, but due to an apparently invalid assignment process, the “owner” of the mortgage is unclear. Thus the lawsuit would determine ownership of the mortgage. A second approach might be for the city to condemn the loan as abandoned property.

Now, pay close attention because this is the important part: In either strategy, the bank will come forward to challenge the city, declaring itself (acting on behalf of the trust) to be the owner. This means that in clouded title processes—unlike the current Richmond plan or extant court cases like Glaski v. Bank of America—the burden of proof should rest with the trusts, and with the banks working as their trustees, to show that they are actually the party with rights to the loan. In other words, this kind of eminent domain approach could force trusts and the banks through which they work to acknowledge that, in fact, they do not own hundreds of thousands of mortgages they claim to own.

Legally speaking, Step 2 is complicated. But let’s say for the sake of argument that the judge indeed decides that the clouded chain of title or “void assignment” means that the trust does not actually own the mortgage, which is the legal precedent we are trying to create. This leads us to…

Step 3: If the trust doesn’t own the mortgage, the next legal question is, well who does? The city is making a claim on the mortgage via eminent domain, but it still has to offer the owner, whoever that may be, fair market value (FMV) in order to take possession.1 Most lawyers we’ve spoken with say that once it has been established that the trust does not own the loan, ownership would revert back one step in the chain, to the aggregator or maybe the loan originator.2 Seems straightforward enough, except that in California and across the country, many of those companies went out of business entirely (see a list of 388 such companies here) and left no successors.3

If it turns out that there is an owner, whether the aggregator or the mortgage originator, we’re back to using eminent domain, as Richmond originally envisioned (i.e., the CARES program, albeit for a single mortgage). It seems predictable enough that whoever has been declared the owner (some sort of entity tied to Wall Street) will push the same kind of court case that has already been filed in Richmond,4 even if said entity is already bankrupt. It also seems safe to assume that every bank in America will be falling over themselves to pay all associated court costs and we’ll be potentially looking at years of litigation. But even anticipating this response, we will have already dealt Wall Street a nasty blow—legal proof that the tens of thousands of trusts that were set up to hold securitized mortgages don’t really own them!

And if no one owns the loan, we move on to Step 4, where things start to get very exciting and very speculative.

Step 4: With no owner, it seems there is a chance that the city would not have to offer FMV to anyone. In terms of legal procedure, the city could then hold the proceeds of the loan in escrow, and pursue a quiet title action: after five years, if ownership on the loan proceeds is still unknown, quiet title could proceed via an “unclaimed funds” argument, and those funds could then legally belong to the city.

Step 5: Once the precedent is established that the city can take possession of mortgages via clouded title/eminent domain, there are many possible routes that Richmond could take. Among them, the city could threaten to initiate the same procedure against a whole set of houses within Richmond, unless the servicers/banks/trusts negotiate satisfactory principal reductions. Another option would be to forego the threat and instead simply take those mortgages and place them in another entity altogether. For instance, (and to end with a provocation) this would be an ideal situation to leverage in order to argue for a public bank. Rather than give those mortgages over to another private company to securitize and gamble with all over again, the city could set up a public bank to service those mortgages, collect payments, etc. Leveraging clouded title to set up public banks has the potential not only to eliminate the blight caused by the foreclosure crisis, but also to use the funds collected to invest in public infrastructure—schools, roads, parks—instead of providing profits to Wall Street and shareholders, as is the mandate of private banks.5

As this brief mention of a public bank suggests, this new twist on the eminent domain tactic has exciting implications. Not least among these is the prospect of finally transferring some of those ill-gotten gains away from the gamblers, who have yet to be punished in any meaningful way for their recklessness with other people’s money, and toward today’s debt-owners, who once imagined themselves to be homeowners. Even if the plan fails, it still has the potential to cause serious tax problems for these trusts. Proof that mortgages were entered into PSAs past the closing date would theoretically eliminate the tax-exempt status (as pass-through entities) that trusts currently enjoy.6 To date, the IRS doesn’t seem to care, and no one seems to have pushed the issue, but suppose some “outraged taxpayers” reported a set of trusts as tax cheats and demanded that the IRS pursue them and give the group the 30% of the taxes and penalties recovered that would be their due!

While the clouded title approach has many legal complexities, and while it is very difficult to tell what might happen once a brave municipality decides to test the waters, we feel confident asserting two things: First, simply the prospect of turning the tables on the banks by forcing them to prove ownership (which they most likely cannot) is itself a significant step in the right direction. Second, as one lawyer we consulted for this article put it:

These are issues of power. Create enough political leverage, and these nebulous and complex issues get resolved in favor of the people. Judges and policymakers have to understand that correct decisions are the only thing standing between them and 40,000 people marching in the street.

And for that reason, we introduce these issues to you, so that you can introduce them to your friends, and if they hit the courts, we can all be ready. See you in the streets.

1 The Eminent Domain Clause of the Fifth Amendment permits the government to appropriate private property, including real estate, personal belongings, and intangible assets, for a public purpose so long as the owner receives just compensation, which is normally equated with the fair market value of the property. This prescription attempts to strike a balance between the needs of the public and the property rights of the owner.

2 Because the “previous owner” has already been paid for the mortgage, one thing that the (current) claimed owner—the trust—can say is that it has what is called an “equitable” right to the loan, since it paid money to the originator to get it.

3 Some of the loan originators may have gone out of business but be in bankruptcy proceedings. If that’s the case, the loan would be an asset in the bankruptcy, hence, the bankruptcy trustee would get control of it and make the decision about whether to sell it, foreclose, etc.

4 Wells Fargo Bank, National Association, as Trustee, et. al. v. City of Richmond, California and Mortgage Resolution Partners Llc, Case No. CV-13-3663.

5 The Bank of North Dakota is a public bank that has existed for over one hundred years and is so successful that even North Dakota’s Republican-dominated government has no intention of purging such a “socialist blight” from its prominent place in the economy of the state.

6 A securitized trust is what’s known as a Real Estate Mortgage Investment Trust, or REMIC, for legal and tax purposes.